“I’m afraid that the following syllogism may be used by some in the future.

Turing believes machines think

Turing lies with men

Therefore machines do not think

Yours in distress,

Alan”

– Alan Turing

Sounds strange? It makes you think? Well, that is the realm of artificial intelligence (AI) philosophy.

Just like any other abstract concept bubbling in the mind of a philosopher, artificial intelligence (AI) too, has bothered and entertained philosophers with a lot of paradoxes, assumptions, and doubts since its advent. It started, perhaps, when Daniel Dennett talked about AI in 1979. He said something like this – I want to claim that AI is better viewed as sharing with traditional epistemology the status of being a most general, most abstract asking of the top-down question: how is knowledge possible?

Well, as much boring, logical, and commercial as we think, or hope, AI to be – AI can get a lot of Meta, a lot abstract, and a lot more complex than what it looks like on the surface.

As to AI, there are two sides to it: Reasoning-based AI or Behaviour-based AI. One dimension is whether the goal is to match human performance or, instead, ideal rationality. The other dimension covers the aspect of a purpose – to build systems that reason/think, or rather systems that act.

That’s where the question of ethics also trickles in. The moral side of AI, the doubts about Robot Ethics, and the highly consequential impact of decisions made by machines on human life- well, it is an iceberg waiting to be drilled into.

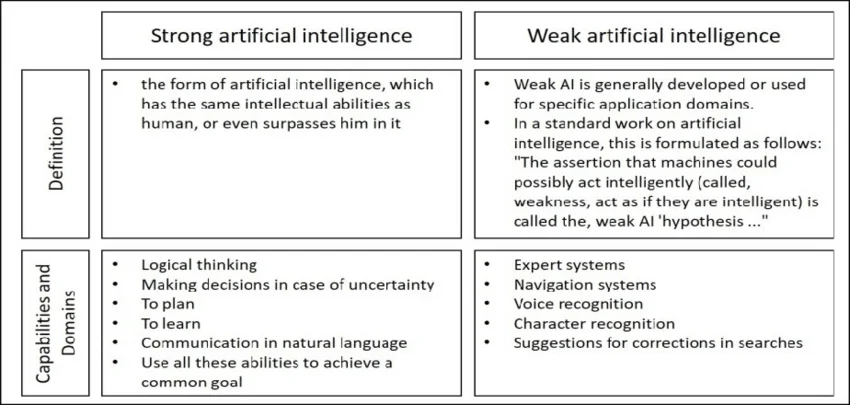

Where all this takes a unique turn is where the road forks between Strong and Weak AI.

‘Strong’ versus ‘Weak’ AI

Simply put, Weak AI is what we see every day. It is the vanilla part of AI where machines can pass the Turing Test or Total Turing Test. It’s where they process information, apply intelligence, learn models and augment humans. Strong or General AI is the next realm where machines could think like humans and need human intervention. It would almost be akin to a universe of artificial persons wherein machines possess all the mental powers and human consciousness. So, Weak AI is like Artificial Narrow Intelligence (ANI). But Strong AI is Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), where a machine gets as smart as humans and can perform any intellectual task that a human being can.

Source: Researchgate

Now how can philosophers resist the temptation to slice Strong AI through their tools? They do, and that’s how various pro-AI and anti-AI proponents emerge.

The Chinese Room Argument against “Strong AI”

This is one such argument in the philosophy of AI. It started with John Searle’s (1980) experiment called the Chinese Room Argument (CRA). It has been designed to overthrow “Strong” AI. Here, Searle is inside a room.

The Chinese Room Experiment

There are native Chinese speakers outside who don’t know that Searle is inside it. Now Searle does not know any Chinese but is fluent in English. When the Chinese speakers send cards into the room through a slot, they have written questions in Chinese. The box sends back the cards to the native Chinese speakers as output. This has been created by consulting a rulebook. For Searle, the Chinese are all gobbledygook. The argument is that sitting inside the box, Searle is like a computer. He doesn’t understand Chinese and is mindlessly moving information around as computers would do.

The Gödelian Argument against “Strong AI”

This is another argument and started with Kurt Godel’s 1930s Incompleteness theorem. As per this theorem- any consistent formal system which can do even simple arithmetic is incomplete.

Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem

There are factual statements in the realm of number theory that cannot be derived from the axioms of the formal system. Hence, some statements, even if they are authentic, are not theorems of the formal system. This is where academics talk about the limits of provability in formal axiomatic theories. Like it is always possible to construct a ‘Gödel statement’ which a given consistent formal system of logic (such as a high-level symbol manipulation program) could not prove. The crux is that the human mind can correctly determine the truth or falsity of any well-grounded mathematical statement (including any possible Gödel statement). Therefore, the human mind’s power is not reducible to a mechanism.

Conclusion

So, is human reasoning too powerful to be captured in a machine? Well, the critics and advocates of AI keep having that war of ideas now and then. The future is a lot of grey matter here.

Interestingly, as John McCarthy, who also coined the term ‘Artificial Intelligence’ in 1956, had warned us well – “as soon as it works, no one calls it AI anymore.”

AI is more than a technology revolution. It is a playground for philosophy. One which, for a change, is not just in mind. It’s in and about the human brain.

India

India  USA

USA